The Great Depression: A Crisis of Intervention and Monetary Collapse

The worst economic downturn in contemporary American history was the Great Depression. Although the New Deal has frequently been credited with saving the economy, this blog post will posit that, based on a closer examination of articles from class, this is not the case. This idea is supported by academics like Christina Romer and Robert Higgs through the lens of economic theory, which suggests that the Austrian theories of monetary expansion and the business cycle, respectively, offer a better explanation for the Depression's beginnings and end. Furthermore, the New Deal did not bring an end to the depression on its own. This post will demonstrate that, in reality, it was taking America off the gold standard.

On The Gold Standard

Since the 1830s, the US has operated on a de facto gold standard, and since 1900, it has operated on a de jure gold standard. The Federal Reserve adopted the gold standard as part of its structure in 1913. According to the law, the Federal Reserve had to convert dollars into gold at a set price of $20.67 per ounce of pure gold and hold gold equivalent to 40% of the value of the currency it issued, which is officially known as the Federal Reserve Note but is commonly referred to as the dollar.[1]

Usually, the Federal Reserve had more than enough gold on hand to support the money it issued. The excess was dubbed "free gold" by bankers. The Federal Reserve needed to have sufficient free gold on hand to cover any redemption requests that might arise in the near future. To move gold from the pockets of the general public (both domestically and internationally) to the vaults of Federal Reserve district and member banks, the Federal Reserve could raise the stock of free gold by raising interest rates, which in turn encouraged Americans to deposit in banks and foreigners to invest in the United States. [2] On the other hand, gold would flow from the Federal Reserve's coffers into the hands of the general public, both domestically and internationally, when interest rates were lowered. When the market collapsed in 1933, it led to the Great Depression. On March 12, Roosevelt took to the airwaves in one of his famous "fireside chats" to bolster confidence in the banking system. [3] But how did the depression begin, according to academics?

The Austrian Framework and the Collapse of the 1920s Boom

The Austrian theory of the business cycle, pioneered by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, argues that economic booms fueled by artificial credit expansion inevitably lead to busts. During the 1920s, the Federal Reserve pursued low interest rates that distorted capital markets and encouraged widespread malinvestment. The illusion of prosperity created by unsustainable credit expansion culminated in a speculative bubble that burst in 1929, precipitating the Depression.

Robert Higgs does not adopt an Austrian lens per se, but reinforces its conclusions by detailing how the crisis fostered structural shifts in governance. In his seminal article, Higgs proposes the "ratchet effect", whereby the state expands its role dramatically during crises but never fully recedes afterward. During the Great Depression, federal intervention, though often ineffective in the short term, permanently altered the relationship between the individual and the state. What began as emergency measures evolved into enduring institutions and bureaucratic norms. As Higgs notes, "post-crisis retrenchment is incomplete; bureaucracies and policies persist beyond their immediate justification." [4]

The crisis created the public perception that only a powerful federal government could resolve widespread economic despair. This ideological shift, initially justified by the emergency, later became normalized, fundamentally altering the American political economy. The New Deal, according to Higgs, thus served more to institutionalize ideological change than to catalyze actual recovery. One such example would be welfare. A short-term solution that was intended to be removed, however, was not, and created a dependency on the government

Romer’s Monetary Interpretation: Recovery via Gold and Expansion

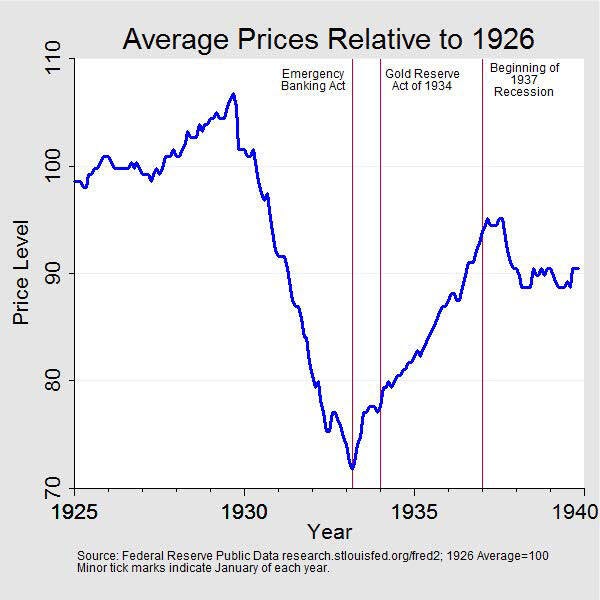

If the Austrian theory best points out the causes of the Depression, Christina Romer provides the most compelling explanation of its eventual demise. In her landmark 1992 article, Romer systematically dismantles the popular claim that New Deal fiscal policy ended the Depression. Instead, she attributes recovery primarily to monetary expansion, mainly resulting from international gold inflows following political instability in Europe.

Between 1933 and 1940, as countries like France and Germany faced war and capital flight, large quantities of gold flowed into the United States. This enabled the Federal Reserve to increase the monetary base. According to Romer, this growth in the money supply directly influenced industrial output and employment. [5] It can be said that it was not Roosevelt’s fiscal interventions, but rather his decision to abandon the gold standard and allow monetary expansion, that marked the turning point in America’s economic recovery.

Romer also emphasizes the role of expectations in economic behavior. By shifting policy in a way that signaled a commitment to reflation, Roosevelt’s monetary moves altered investor and consumer confidence. "Expectations of future monetary expansion," she writes, "played a key role in the revival of private spending." [6]

Synthesis: Crisis, Theory, and Transformation

Therefore, a synthesized narrative based on Romer's monetary analysis and Austrian business cycle theory provides a cogent explanation of the Depression. Due to mistakes made by the Federal Reserve, the artificially inflated boom of the 1920s collided with the world's precarious financial system, causing widespread liquidation and unemployment. As Higgs's "ratchet effect" shows, the state's response, particularly during the New Deal, did not end the crisis but instead led to a sustained growth in governmental authority. Romer would argue that the recovery from the Great Depression was largely spurred by the abandonment of the gold standard and the ensuing monetary expansion. [7]

Conclusion

In the end, monetary loosening and global gold inflows, not government spending, reversed the Depression's course. This interpretation challenges the Keynesian orthodoxy and presents a cautionary tale: crises often invite centralized solutions that linger long after their necessity has passed.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Gary Richardson, Alejandro Komai, and Michael Gou, “Roosevelt’s Gold Program | Federal Reserve History,” Www.federalreservehistory.org, last modified November 22, 2013, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/roosevelts-gold-program.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat on the Banking Crisis.” March 12, 1933. In The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, vol. 2, 1933. Edited by Samuel I. Rosenman, 66–74. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

[4] Robert Higgs, "Crisis, Bigger Government, and Ideological Change: Two Hypotheses on the Ratchet Phenomenon." Explorations in Economic History 22, no. 1 (1985): 1–28. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/liberty.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/crisis-bigger-government-ideological-change-two/docview/1305246411/se-2.

[5] Christina D. Romer, “What Ended the Great Depression?” The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123226.

[6] Ibid., 779

[7] Ibid., 768

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Higgs, Robert. "Crisis, Bigger Government, and Ideological Change: Two Hypotheses on the Ratchet Phenomenon." Explorations in Economic History 22, no. 1 (1985): 1–28. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/liberty.edu?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/crisis-bigger-government-ideological-change-two/docview/1305246411/se-2.

Jacobson, Margaret M., Eric M. Leeper, and Bruce Preston. “Recovery of 1933.” American Economic Review: Insights 4, no. 2 (June 2022): 203–22. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20200304.

Richardson, Gary, Alejandro Komai, and Michael Gou. “Roosevelt’s Gold Program | Federal Reserve History.” Www.federalreservehistory.org. Last modified November 22, 2013. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/roosevelts-gold-program.

Romer, Christina D. “What Ended the Great Depression?” The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123226.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. Executive Order 6102: Requiring Gold Coin, Gold Bullion and Gold Certificates to Be Delivered to the Government. April 5, 1933. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-6102-requiring-gold-coin-gold-bullion-and-gold-certificates-be-delivered.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. “Fireside Chat on the Banking Crisis.” March 12, 1933. In The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, vol. 2, 1933. Edited by Samuel I. Rosenman, 66–74. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

text.

Create Your Own Website With Webador